Unit 7

How David Eaves teaches Unit 7 (part 1)

Open Data, the Promise - and where to from here?

What is this page?

This is a detailed breakdown of how David Eaves, a Lecturer at the University College London's Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (UCL IIPP), teaches the contents of Unit 7 of the open access syllabus developed by Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age. Read how part two of Unit 7 is taught here.

This page is part of a series of twenty-five classes that David developed originally for the Harvard Kennedy School's master and executive education programs, where he taught for eight years, and are now taught at UCL's master and applied learning programs.

We believe presenting diverse ways to teach the syllabus will help others adopt and teach the material in various contexts. See here how Konstanz University's Prof Ines Mergel teaches the same unit.

Who is this page for?

This page was developed for university faculty who teach public administrators or master's levels students in public policy and public administration. This material may also be suitable for teaching to upper year undergraduates.

Class Overview

🚨 This class is more lecture than discussion format than many of David's other classes. The class outline below will reflect this fact and so may read differently that previous course outlines.

As previously discussed in Units 2 and 5, data is the memory of government. Data is how governments track and manage assets over time and remember to whom and when it should deliver many modern day services. Traditionally this data has been closely held by governments, hard to access not only by the public but even by public servants in other parts of the same government. Over the past two decades the idea that government data is, in of itself, a public good has been ascendant. This idea holds that some, or even a great deal of government data should be made available to the public openly and freely in support of institutional transparency and public and private sector innovation.

In this class students will be introduced to the idea of open government data. What is it? And why has it - as an idea - spread so widely? In addition, students will explore why local and national governments have open data portals and open data strategies. The discussion will also seek to engage in the institutional barriers to making data open and discuss what policy goals open government data supports and hinders. Finally, the class will also walk through frameworks for thinking about where and how has open data had an impact. These are the issues this first class on "Openness" will tackle. The subsequent class will explore two different domains: open source and working in the open.

This Class' Learning Objectives

By the end of this class students should be able to:

Explain what open data is

A high level history open government

Use a simple framework for assessing the impact of open data

Explain the motivations that governments can have to work in the open

How this class relates to the Digital Era Competencies

💡 This class has a specific focus on Competency 6 - Openness. See all eight competencies here.

Assigned Reading and Practical Resources

As they work through the readings in advance, students should have in mind the following questions to help them prepare for class:

What benefits - if any - might opening up data create for government? What about for society more generally?

Why have governments historically been reluctant to share data with the public (or even internally)? Is this fear well grounded?

What risks exist to opening data? How could those risks be managed?

To what degree is transparency in government an inherent good and how should it be balanced with equity and access?

Core Reading (Required):

It's the icing, not the cake: key lesson on open data for governments (2011), Article by David Eaves

Open data and health care: Beggar thy neighbour (2012), Article by Sean Macdonald for The Economist

Resources Reading (Required)

The 8 Principles of Open Government Data (2007), List created by thirty open government advocates

Advanced Reading (Optional)

Out of the Box (2015), Article published at The Economist

The Open Data Barometer, Dashboard produced by the World Wide Web Foundation

Detailed Class Breakdown

The segments below describe the dynamics of each part of the class. The videos were edited to only display the most relevant parts of each segment:

Segment 1 - What is Open Data? – 10'

Purpose of this Segment

Today, many governments have open data strategies to make government data available. But what is open data? In this segment, students are presented with two definitions of open government data, which help establishing a common ground for the rest of the class.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

This segment starts with the question "What is open data?" Students gives their opinions before David shares two perspectives on the topic.

The first definition comes from a self selected group of activists and academics who, in 2007, came up with 8 principles that define open data: complete, primary, timely, accessible, machine processable, non-discriminatory, non-proprietary, license free. This group - which was both US centric and not particularly diverse - sought to establish a definition that would support greater transparency into government.

David - who had been working on open data issues around the same time - had created his own definition when explaining the concept to policy makers and politicians. In his view, open data can be simplified in three core ideas, that open data must:

be accessible - one must be able to find it easily

be in a machine readable format - one must able to play with **and use the data

be licensed to be repurposed - that any new products or insights one makes can be shared with others

In David's opinion, this third idea is critical and usually not highlighted in the discussion around open data.

⚠️ Instructors can choose their alternative definitions. The main goal here is to provide students with a clear and simple definition that can serve as a foundation for the rest of the class.

Segment 2 - New Expectations – 10'

Purpose of this Segment

The rise of the idea of open government data is, in part, a response to new expectations created by the rise of the internet, the networked society and the knowledge economy. These phenomena are reshaping both how much and how quickly the public expects to gain access to data and information - including from the government. The purpose of this segment is to provide an overview of some of these new expectations and a sense of how wide spread open data policies have become.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

To illustrate the new expectations around open data in governments, David refers to a Sir Tim Berners-Lee Ted Talk, the creator of the World Wide Web. In the talk, Sir Berners-Lee asserts that a core goal of the web was to enable people to share information, and in particular: data. While grateful for the web's innovations Sir Berners-Lee's talk is essentially a plea to scientists, public officials and others to make more raw data available on the web for everyone to use and build upon.

This plea is, in many ways, astounding given what might have been possible only 20 years earlier. It is a reflection of the dramatic impact of the internet and the web on many people's ability, and thus expectations, to access information. Today, it takes on average 30 milliseconds to return a Google search result and often will the results being both accurate and helpful. This is radically reshaping how easily people expect to find government information. Open data portals - places where one can search of various government data sets - are in part attempt to close this expectation gap.

To demonstrate how wide spread the practice of making government data has become, David suggests an experiment. He asks students to Google: "Your home country/state/city + Open Data". Students are often surprised to see that their governments already have open data portals.

💡 Many students remain completely unaware of how much data is available to them. Simply making them aware can be helpful for other courses as they can use government data in their research for other classes. David finds it useful to have examples from local and national governments, as well as international organizations - like the World Bank's open data portal - available to share with students.

Segment 3 - History and Context – 20'

Purpose of this Segment

In this segment David attempts to place open data into a larger narrative of public access to government information and institutional transparency. In particular, he seeks to highlight the important role technology has played in shaping government transparency movements and access to information policies.

💡 While this section focuses on the history of public access to government information it is also an excellent example of how technologies can help fundamentally new policy options emerge. This can be a useful conversation from a policy analysis and emergent technology perspective.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

Access to Information and Open Data

To start, David draws a quick distinction between the access to information advocates and open data advocates. Access to information advocates have been critical of open data advocates as open data policies have not, traditionally, come with any legal guarantees or protections. This has led some access to information advocates to assert that open data is all technology and not values while their own movement is all about values and not technology.

In David's opinion, the two movements are quite similar but at different stages of maturity. They share a common goal of improving access to public information, and differ only in the technologies they use and in how much legal protections they've been able to garner to date. For David both open data advocates and access to to information are driven by values, and possibly more importantly, both are shaped by the key technology of their era.

👉🏽 One idea to consider during this session is to explore the motivations of access to information and open data advocates. These motivations can be complex ranging from government accountability and transparency, to a desire to improve government services, private sector interest to name a few. The impact of these policies is worth exploring as well. Who benefits from FOIA and open data? For example, some of the heaviest users of FOIA are private companies researching the services competitors sell to government so as to better mimic or compete with them.

The background

The first attempts to make government information public started in 1766 with the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act. It would take a couple of centuries for a law with a similar goal - the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) - we be passed in the United States in the 1960s.

One theory for why FOIA came to pass in the 60s was the Watergate. This American political scandal created public appetite for government transparency and accountability. However, one challenge to this theory is to ask: why Watergate? Why hadn't corruption scandals prior to the 1960s created a similar public pressure for FOIA legislation?

David suggests that while Watergate created necessary political conditions, Xerox's invention of the photocopier in the 60s was essential to the success of FOIA. It would have been impossible to make public information available as imagined in FOIA without photocopiers! Access to information advocates may have values, but they are also dependent on a technology - paper and photocopiers.

Why this matters

FOIA's development is one example of how technologies can shape policy options and government processes. It's also a window into the critical role process plays in an organization and the power that comes to those who control those processes. It also hints at a future where processes are increasingly encoded into digital systems, how much power those who control such systems will have.

It is also why David is critical of how governments have tried to tackle the issue of transparency. Regulations often focus on how to make information and data available as an after thought. A more productive approach would be to think about how transparency could be baked into systems by leverage and standardizing procurement practices.

Segment 4 - Where are we? - 20'

Purpose of this Segment

In 2010 the open government data movement gathered enormous momentum. Now 10 years later, what have we learned? What policy goals can open data help address? What successes has open data created governments, or the public? This segment will walk through a four stage framework for evaluating the impact of open government data programs.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion and Examples

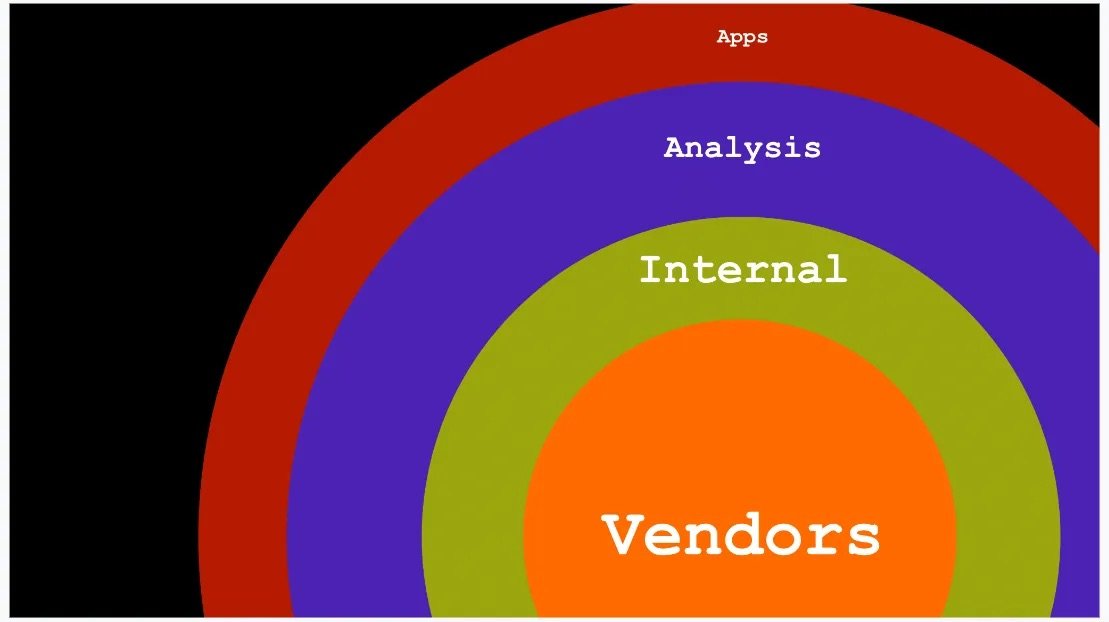

David introduces four uses of open data, one a time, during this segment.

Applications

In the early days of open data (around 2007-2010) governments were enthralled with hosting hackathons and allowing software engineers to create applications that would create public value. There are examples of successful applications using open data such as google maps consumption of public transportation data. However, the idea that hundreds of software applications will be written for free for the public is not sustainable. First, the idea of "if you build it (an open data portal), they will come (software engineers)" is hard to sustain because software development skills remain relatively rare. Moreover, building and maintaining even a relatively simple applications is a real labor of love - to say nothing of one that thousands or millions of citizens or government officials might come to depend on.

This isn't to say that having software developers tinker and build with government data is not useful. It can help governments understand new opportunities for using their own data and serve as a research and development phase for what applications - with the right institutional and financial support - might be worthy of more exploration.

💡 One goal in this section is to have students recognize how the goals of an open data program can shape who is included (software developers) and who may be excluded (everyone else). And what policy goals, if any, is the open data program seeking to address?

Analysis

While software development skills remain relatively rate, the ability analyze and play with data using excel - while not ubiquitous - is more prevalent. In addition, a good data analysis can provide powerful insights without significant ongoing maintenance costs. To illustrate, several examples of data analysis are presented. Some are simple insights from a spreadsheet while others - such as as the COVID-19 dashboard created by John Hopkin's University - are more complex and resource intensive. But in each case someone has taken data and created insights or value out of it. For example, all the data it used the Johns Hopkins dashboard is drawn for external sources but it still creates real value for the world.

The point here being that, while not as interactive as applications, having the public analyze government data remains an under-appreciated source of value with enormous potential.

🙏 We all owe Beth Blauer, Executive Director of the Center for Civic Impact at Johns Hopkins University a debt of gratitude for her amazing work and leadership in helping create the John Hopkins COVID-19 dashboard. This dashboard became the global source of truth about the scope and severity of the pandemic in its early days. Beth has been a long standing expert on the use of data in operations management.

Internal uses

Interestingly, one of the most powerful benefits of open data is its capacity to increase the use of data inside the organization that is publishing it. Over the past decade David's has interviewed numerous CTOs and other stakeholders responsible for launching open data portals. In these conversations he learned that, on average, 30-50% of visitors to open government data websites are public servants within the publishing institution.

Historically governments have been reluctant to share data not only the public, but with other parts of government as well. Sharing data was often burdensome and bureaucratic process.

An open data portal removes these barriers for public servants. In addition, given most government data is designed to be used by public servants, this audience is among the best positioned to leverage this data. As a result open government data can help governments be more data driven in their decisions by making its own data more accessible to its public servants.

Vendors

One challenge for governments their operations have come to relay on highly customized or configured software systems. As a result the underlying data in those systems - the 'memory' of government - gets saved in unique data schemas or worse, proprietary data formats. This makes extracting the data to either simply analyze or, more ambitiously, migrate to a new software system, difficult to impossible.

One possibility for open government data is it could lead to greater standardization of government data. This in turn might increase not only the interoperability of government systems but also the portability of a service. If governments could more easily extract data from one vendor's offering and upload it into another, it might reduce 'vendor lock in' and reduce IT costs.

Segment 5 - Open Data - Where to from here? - 10'

Purpose of this Segment

In the previous segment, students were presented with a view of the current opportunities that open data enables. But what future opportunities can open data unlock? In this segment, David shares his vision for how standardization can commoditize open data and allow for revolutionary new uses of data.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

To start this segment, David shares an image of a boat and asks students to guess its significance. The image is of the world's first container ship. The picture represents the revolutionary role the invention and standardization of the shipping container played in globalization. This story is told in the book "The Box", by Marc Levinson.

David believes the next needed phase of the open data movement is standardization. This would allow data from multiple institutions to be easily merged and analyzed or exchanged across institutions. Standardization would open up new possibilities (and risks) to focus and scale public goods.

In addition, openness and standardization could dramatically change the way public servants work. Today, ownership or control of data can be a source of power in a bureaucracy. But in a world of open data power might shift to those who can make creative use of available data. And the available of that data - particularly if it could be compared across jurisdictions - could make governments more accountable for their policies.

Common questions from students faculty could prepare for:

- Is there any criteria for when data should be shared or not?

How can you get support teaching this unit?

We're dedicated to helping make sure people feel comfortable teaching with these materials.

Send a message to mailbox@teachingpublicservice.digital if you want to book in a call or have any questions.

You can also connect with David on LinkedIn.

What are your rights to use this material?

We have developed these materials as open access teaching materials. We welcome and encourage your re-use of them, and we do not ask for payment. The materials are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

If you are using any of our syllabus materials, please credit us on your course website using the following text:

We are proud to use the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age syllabus in our curriculum and teaching. Developed by an international community of more than 20 professors and practitioners, the syllabus is available open-source and free at www.teachingpublicservice.digital

Why was this page created?

This teaching material forms part of the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age project. Read more about it here.

Acknowledgements

David Eaves would like to note that this material was made possible by numerous practitioners and other faculty who have generously shared stories, pedagogy and their practices. David is also grateful to the students of DPI 662 at the Harvard Kennedy School for enriching the course and providing consent to have the material and questions shared. Finally, an enormous thank you must be given to Beatriz Vasconcellos, who helped assemble and organize the content on this page.