Unit 8

How David Eaves teaches Unit 8 (part 1)

Digital Transformation Strategy

What is this page?

This is a detailed breakdown of how David Eaves, a Lecturer at the University College London's Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (UCL IIPP), teaches the contents of Unit 8 of the open access syllabus developed by Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age. See how parts two, three and four of Unit 8 are taught.

This page is part of a series of twenty-five classes that David developed originally for the Harvard Kennedy School's master and executive education programs, where he taught for eight years, and are now taught at UCL's master and applied learning programs.

We believe presenting diverse ways to teach the syllabus will help others adopt and teach the material in various contexts. See here how Konstanz University's Prof Ines Mergel teaches the same unit.

Who is this page for?

This page was developed for university faculty who teach public administrators or master's levels students in public policy and public administration. This material may also be suitable for teaching to upper year undergraduates.

Class Overview

Digital era government is not just about developing new practices and capabilities. There exists a larger question of high new practices and technologies will cause a rethinking of how government institutions are structured and managed. In short, how does a government adapt from an analogue to a digital era?

For many governments an emerging "north star" is the view of platform government, as described in the Unit 2 of this course. With so much work to do and so many systems, processes and services ripe for transformation, where should a government start? This class explores divergent digital transformation strategies taken by various governments around the world. It also examines the traditional role played by government IT departments, and how it both enables and hinders public sector institutions ability to transform themselves for the digital era.

To help public leaders better understand possible transformation strategies this class will provide frameworks to think about different digital units' focuses, the nature of changes that government want to implement and for theories of change towards a 'government as a platform' approach.

This Class' Learning Objectives

By the end of this class students should be able to:

Explore approaches to digital transformation

Map these approaches to models

Enumerate barriers that exist to new digital practice

How this class relates to the Digital Era Competencies

💡 This class has a specific focus on Competencies:

Competency 5 - Barriers

Competency 3 - Multidisciplinary

Competency 6 - Openness

See all eight digital era competencies here.

Assigned Reading and Practical Resources

As they work through the readings in advance, students should have in mind the following questions to help them prepare for class:

Why is “IT” considered unimportant in government (and in the teaching of public policy/administration)?

What strategies and approaches are governments taking to “doing” digital transformation?

What are digital service teams? How are they seeking to enable digital transformation?

Is there a difference about how we think of IT from 20 years ago and IT presently?

Core Reading (Required)

The Theory of Modern Bureaucracy and the Neglected Role of IT, Chapter 1 in Digital Era Governance: IT Corporations, the State, and e-Government (2006), Book by Patrick Dunleavy, Helen Margetts, Simon Bastow, and Jane Tinkler

Digital Service Teams: Challenges and Recommendations for Government (2017), pages 8-11, Report by Ines Mergel for the IBM Center for The Business of Government

The End of the Beginning for Digital Service Units (2018), Blog Post by David Eaves

Advanced Reading (Optional)

Digital Service Standards, Guideline by UK's Government Digital Service (GDS)

Agile Delivery, Guideline by UK's Government Digital Service (GDS)

The Difference between 18F and USDS (2015), Blog post by Ben Balter

Detailed Class Breakdown

Class plan: 75 minutes

Segment 1 - Optional: previous assignment debrief - 10'

The goal of this segment is to provide general feedback to the class about a previous assignment.

Throughout this course, students are required to complete multiple assignments. Even though students get individual feedback, David likes to take time to share and review some of the best assignments as well as discuss common challenges students had in their submissions. The purposes are to:

Acknowledge students who did high quality work and set course expectations by showcasing peers works

Demonstrate that assignments are carefully analyzed and good work is valued

Clarify grading criteria

Help clarify concepts that didn't seem to be clear

To reinforce these messages David encourages students - if they feel comfortable - to share links to their assignments with the class.

Segment 2 - Why does Technology Fail? - 35'

Purpose

In 2020 a shocking number of digital technology projects fail. The Standish Group, a consulting firm that regularly publishes reports looking at the success rate of IT projects, concludes that 83.9% of IT projects fail partially or completely. This number should be treated with some skepticism as the rigor and methodology of the report are opaque. But even as a "ballpark" figure it remains a sobering statistic.

Applied to the public sector it means that vast resources - money, time and talent - go wasted every year To improve the success rate, public leaders should understand the root causes that drive these failures. The goal of this segment is to explore these root causes.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

To start, instructors can show examples of digital projects that failed. The objective is to highlight the volume and scale of wasted resources - which range from small local projects to massive federal initiatives. In this class, David shares the examples of Canada's Phoenix System, UK's NHS IT System, and FBI's Case Management System.

💡 As an assignment David sometimes ask students to find IT failures in their home city, state or country. This can be a nice way to find more diverse or locally relevant examples. Students always find examples and it can be a nice way to bring the material back to a context they know and care about.

But why do digital projects fail? This is an excellent starting question for a class discussion. Hopefully answers will draw on ideas and models outlined in the pre-class readings and the instructor can pin point connections.

After the discussion, instructors should present their main hypotheses. David likes to highlight three:

Key stakeholders - particularly senior managers but also (painfully) schools of public administration - have not focused on the oversight of IT. This is, in part, reflected by reviewing the curriculum of public policy and public administration programs. According to a research by Morçol et al (2020), only 11% of MPP programs have tech related subjects in their core courses.

Most careers paths don't reward the development of digital era administration skills. Promotion paths in many public organizations reward policy specialization and less public administration skills generally and certainly not domain knowledge of digital or IT skills specifically.

The skills, capabilities and responsibilities needed across the bureaucratic hierarchy to deliver, manage and oversee digital projects are still emergent (as we've been exploring in TPSDA!). The traditional role of IT of providing support or technical services is necessary but not sufficient. While determining who should possess these new capabilities and skills and where they should sit involves significant organization change challenges.

Segment 3 - Digital Unit Teams- 15'

Purpose

The challenge of bringing in new digital competencies and capacities into government is not dissimilar to the challenge of bring any new competency and capacity. A challenge of innovation and organizational challenge around which there is a solid literature. (Indeed, one of our purposes, as instructors, should be to explore such literature while presenting cases that are digital era relevant.)

A common strategy for governments that lack a competency or capacity is to create a specialized group that acquires, nurtures said competencies in the bureaucracy while protecting it from internal forces that might reject it. In the past decade this strategy has manifested itself in the digital government space through the creation of digital units or teams that sit apart from the traditional IT function. How are these units created? And what should their role be? This segment discusses these questions.

Video of David teaching this segment

Discussion

Digital units can emerge for different reasons. Understand this variation can be helpful for students to leverage opportunities to help create moment for pulling in new capabilities and capacities. In this class, David shows a few examples of what caused some countries to pursue a digital transformation strategy and/or set up a digital service unit:

One defining traits shared by many digital service units is these teams are separated from the traditional IT function. Even more importantly, unlike IT, which often sits in a support service function that is perceived as non-strategic by the apex, these units are incorporated into the technostructure - which often provides oversight and sets standards over the organization and is proximate to more influential decision makers.

Although these groups have similar goals - to create and diffuse new practices - their powers and focus can vary widely. To illustrate, David argues that a team may have significant powers to compel ministries and government stakeholders to adopt to practices by say, overseeing all IT spending, or it may have few powers and need to be consultative and persuasive by working in the open and modeling best practices.

Teams may also focus on improving the experience for users by concentrating on improving a services front end. Alternatively they may build out new platform services - like gov.uk/notify or 18F's federalist project - that seek to radically reduce costs and improve the scale of good practices and services.

Segment 4 - What Change Looks Like - 15'

Purpose

Another challenge is to ascertain how much "force" is required to shift government practices. Does one believe that a small demonstration project will create appetite among other stakeholder and create a reinforcing positive feedback loop? Or that left to their own devices government agencies will revert to a substandard default approach to delivering services? This too might inform your strategy and how one might invest resources.

In this segment, David presents these complementary methods and illustrates them with worldwide cases.

Video of David teaching this segment

📢 In this video, we included the Q&A session after class.

Discussion

The most common approach to tackle digital projects is to reflect on the nature of the problem that governments want to tackle. For example, a problem can be purely technical, such as the inability to translate paper health records into digital. For such a project, a change would look linear: a solution for the problem is developed, government applies the solution and moves on to another stage. But maybe a technological change requires a constant push to not regress to status quo. This is the case, for example, of the Calfresh case seen a few classes ago.

Understand how much "force" will be required may shape one's strategy and approach.

📢 For a sobering example, consider this paraphrased quote from a software developer embedded in a national government's digital service team: "We are so convinced that if we build something good - technically sound, user focused with a strong UX and UI - it will create more demand for our approach. I think one sobering realization is that many public servants may not even be equipped to identify what good looks like and so all that effort could be for naught."

To make this clear, David presents four types of change that can be applied to technology projects:

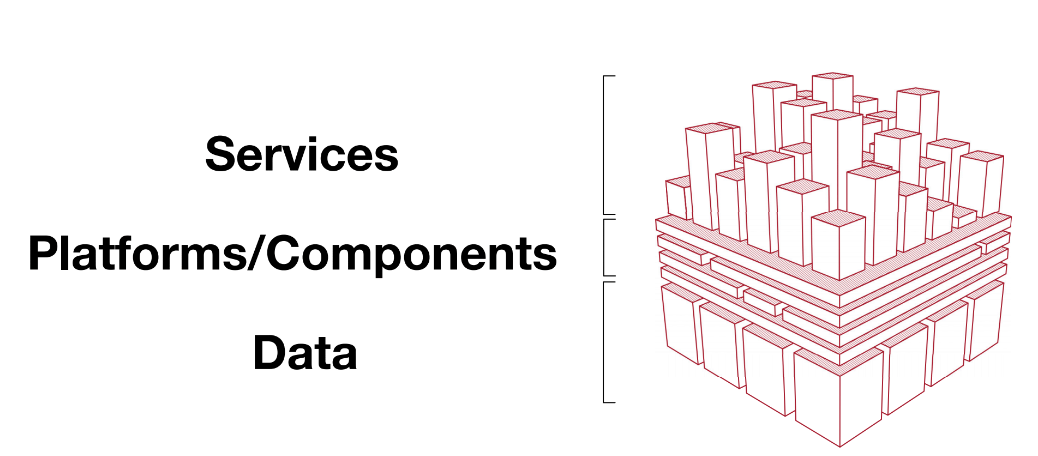

At this point David refers back to the "north star" representation of government presented in the second class of this course (Government as a Platform). It is a simplified version that identifies three layers of technology that represent how core government activities could manifest in a digital era: data, shared components and services (this builds on work conducted along with Ben McGuire and Richard Pope).

David presents a framework with five different approaches governments are adopting to build out this vision of digital era government. These five strategies serve two purposes. One is to inform students about different strategies that have been used by technology groups within government. The second is cause students to reflect on which model is most feasible given a specific cases political and institutional constraints, as well as the capacities of those driving the change.

The five theories of change are the following:

1) Come in High Establishes design and service standards across the government to create a consistent digital experience for citizens. In defining and pushing these standards across the government, this strategy changes how government services are delivered and consumed by placing the users' experience at the center. Come in High places a premium on user-centered design and uniform delivery standards as a way to enable cultural change across the government. Example: UK's GDS

2) Come in Low Establishes data and technical standards that promote interoperability across government ministries. Individual ministries connect to one another through common data exchange layers and unique identifiers. Ministries are able to define their own systems architecture so long as they plug into the common data exchange layer. Come in Low places a premium on privacy and security of citizen data, unique identifiers promoted through a once-only policy, and canonical datasets that standardize information across the network. Example: Estonia's X-Road

3) Land and Expand Develops a new digital solution for a specific use-case with the intent of applying either the approach or the technology to other government services. As the solution expands, services can be consolidated into a single interface or connected through API endpoints, both of which increase interoperability and accessibility between ministries. An example is Aadhaar, which initially “landed” as an authentication tool for food subsidies and “expanded” to become a core component of other government services. Land and Expand places a premium on building out modular components, design patterns, and canonical databases that will be repurposed and applied to other areas of the government. Example: Argentina's Digital Drivers' License.

4) Shared Components/Infrastructure Creates and provides tools that abstract away common functions across ministries. Whether through procurement or in-government development, this strategy reduces a ministry’s workload and leapfrogs it’s existing capabilities. Examples include the UK’s citizen-messaging system, Notify, the US’ single sign-on system, Login.gov, and India’s unified payments infrastructure, UPI. Shared Infrastructure places a premium on offering centralized services that reduce duplicative efforts across a government. Example: India's Aadhaar and MOSIP.

5) Open APIs Establishes and promotes the practice of ministry attaching endpoints to their data registries, opening access to other ministries across the government. By having requiring government agencies publish their data registries, but not to conform to a common standard, this strategy does not push a single information architecture. Open APIs places a premium on ministries building off one another by decentralizing information, opening access, and minimally disrupting existing services.

Instructors should highlight that governments try a few approaches at the same time, but it is not effective to be deciding on a strategy case by case because it's not likely to lead to major transformations. Instead, it is important that one major theory of change is chosen and set as the north star for the digital strategy.

Common questions from students faculty could prepare for:

- Until when is the digital versus IT problem likely to persist?

- How much of digital transformation has to be a policy shift versus management shift?

- How to make organizations less reliant on individual stakeholders/ champions?

How can you get support teaching this unit?

We're dedicated to helping make sure people feel comfortable teaching with these materials.

Send a message to mailbox@teachingpublicservice.digital if you want to book in a call or have any questions.

You can also connect with David on LinkedIn.

What are your rights to use this material?

We have developed these materials as open access teaching materials. We welcome and encourage your re-use of them, and we do not ask for payment. The materials are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

If you are using any of our syllabus materials, please credit us on your course website using the following text:

We are proud to use the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age syllabus in our curriculum and teaching. Developed by an international community of more than 20 professors and practitioners, the syllabus is available open-source and free at www.teachingpublicservice.digital

Why was this page created?

This teaching material forms part of the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age project. Read more about it here.

Acknowledgements

David Eaves would like to note that this material was made possible by numerous practitioners and other faculty who have generously shared stories, pedagogy and their practices. David is also grateful to the students of DPI 662 at the Harvard Kennedy School for enriching the course and providing consent to have the material and questions shared. Finally, an enormous thank you must be given to Beatriz Vasconcellos, who helped assemble and organize the content on this page.