Unit 3

How David Eaves teaches Unit 3 (part 1)

Learners vs Planners: Agile vs Waterfall

What is this page?

This is a detailed breakdown of how David Eaves, a Lecturer at the University College London's Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose (UCL IIPP), teaches the contents of Unit 3 of the open access syllabus developed by Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age. Read how part two of Unit 3 is taught here.

This page is part of a series of twenty-five classes that David developed originally for the Harvard Kennedy School's master and executive education programs, where he taught for eight years, and are now taught at UCL's master and applied learning programs.

We believe presenting diverse ways to teach the syllabus will help others adopt and teach the material in various contexts. See here how Konstanz University's Prof Ines Mergel teaches the same unit.

Who is this page for?

This page was developed for university faculty who teach public administrators or master's levels students in public policy and public administration. This material may also be suitable for teaching to upper year undergraduates.

Class Overview

Over the past one to two decades 'agile' project management methodologies have become increasingly popular in the tech sector. These 'agile' approaches take a more adaptive approach to a problem, compelling creators to test their products frequently with users in quick iterations (sometimes called sprints). The idea is based on the assumption that the unknown unknowns of a project are vastly greater than either knowns or known unknowns, meaning it is critical that plans, approaches and even a determination of what will ultimately work should remain flexible.

This approach runs in sharp contrast to how governments prefer to run - with a strong emphasis on planning and the belief that any unknown unknowns can be determined and accounted for before any work begins.

In the first part of this class students engage in group exercises to learn what is particular to each project management methodology and when to use them. The second part focuses on the implications the rise of 'agile' approaches for the public sector.

This Class' Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture students should be able to:

Distinguish between waterfall and agile project management practices and describe some of its core features

Decide when to use each project management practice

Describe some of the characteristics of 'Fake Agile' projects whereby traditionally managed projects and overall governance appropriate the language of iteration but not its practices or impact

Describe some of the systemic barriers to agile usage in government

How this class relates to the Digital Era Competencies

💡 This class has a specific focus on Competency 4 - Iteration. See all eight Digital Era Competencies here.

Assigned Reading and Practical Resources

As they work through the readings in advance, students should have in mind the following questions to help them prepare for class:

Think of projects that you have worked on over the past couple of years. Identify one where a waterfall approach was more appropriate and one where an agile approach was more appropriate.

In what ways do agile approaches allow a project to work more quickly? In what ways do they require you to work more slowly?

What institutional barriers exist that make adopting an agile approach difficult? How could you enable your staff to adopt some or all elements of an iterative or agile approach despite these barriers?

Required Core Reading

Agile vs. Waterfall, Webpage produced by Jonathan Rasmusson

Agile: A New Way of Governing (2020), Article by Ines Mergel, Sukumar Ganapati, and Andrew Whitford

Practical Resources

Agile Delivery, Webpage by UK Government Digital Service (GDS)

United States Digital Services Playbook, Playbook by the US Digital Service

GOV.UK's Agile Delivery Service Manual, Service Manual by GOV.UK

Optional Advanced Reading

The New Practice of Public Problem Solving (2019), Article by Anne-Marie Slaughter and Tara McGuiness for the Stanford Social Innovation Review

Escaping the myth of digital government (2017), Article by Jerry Fishenden and Cassian Young

Healthcare.gov and the Gulf Between Planning and Reality (2013), Article by Clay Shirky

Measuring the Benefits of your Service, Article by UK Government Digital Service (GDS)

The Agile Manifesto (2001), Manifesto by Martin Fowler and Jim Highsmith

Also see the Twelve Principles

Agile Practices Timeline, Webpage by The Agile Alliance

[Some Thoughts on Design Research, Agile, and Traps](https://charleslambdin.wordpress.com/2020/03/11/some-thoughts-on-design-research-agile-and-traps/#:~:text=Design is not about creating,“derisk” the decisions made.) (2020), Article by Charles Lamdin

Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic ****(2020), Article by Marijn Janssen and Haiko van der Voort

Detailed Class Breakdown

Class plan: 75 minutes

See David's slides for this class.

The sections below describe the dynamics of each part of the class:

Segment 1 - Introduction and First Exercise: Waterfall – 25'

The goal of this section is to make students internalize what waterfall management methodologies are and when it's appropriate to use each them.

🙏 *The "Go West" exercise outlined below was developed by Matt Andrews at the Centre for International Development at the Harvard Kennedy School. More on the exercise can be found in Chapter 6 of Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action by Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock, Oxford University Press, 2017. ***We are grateful to him for letting us use and adapt it.

📢 (There is an alternative - in person only - approach to teaching this class using the spaghetti exercise for which materials are forthcoming)

Purpose of this segment

Waterfall-like approaches are a traditional way of project management that de-risks work by emphasizing planning and research in advance of starting any work. Gantt charts are a favored tool of Waterfall-like approach. While often criticized by those in the consumer tech space in there are numerous cases where 'waterfall' like approaches are most appropriate. The purpose of this section is to make students aware of when waterfall is more advantageous.

Video of David teaching this segment

Exercise

In this first of two exercises, students are split into groups of 4 or 5. Their instructions are straightforward:

They must plan a road trip from St Louis, Missouri, to Los Angeles, California.

Their goal is to arrive as quickly as possible.

They will have ten minutes to create their plan. It should include items like their route, what vehicle they will use and other logistical issues

Finally, they should also briefly document their plan to share with the class, specifically:

Strategy - What roads will the group take? What cities will they pass through?

Timeline - How long will it take?

Milestones - What are the day-by-day set of milestones (what they are expected to do each day)?

Two slides. The first says "Imagine your team is currently in St Louis, Missouri and needs to get to Los Angeles, California, by car ASAP. The other picture is a contemporary road map of the USA.

For this first exercise it is okay for students to access the internet and use any tools they would like. However, it is worth stressing that students must drive (I've had students plan to drive their car onto a plane and fly to the west coast). A really good team will plan not just their route, but do research on the type of car they plan to use, think of bathroom breaks - in short, thoroughly plan out their journey with a reasonable degree of confidence.

Debrief and Discussion

In the debrief, students commonly share that they used Google Maps or Waze to plot the shortest route, strategized how to rotate drivers to maximize time on the road and even pick the most effective car.

Students should then reflect on why they are able to create such a precise plan, with specific sequenced activities. The discussion should showcase how their plan likely has detailed timelines, milestones and deliverables. It can also benefits from some certainty. The terrain and roads are known, speed can be calculated with fair certainty. And while their approach has a high probability of success. it is also rigid - a plan that has one going through Denver will not easily adjust to taking one through Dallas. A unanticipated roadwork delay may cause them to hit rush hour traffic they hoped to avoid through timing and planning. As the conversation evolves, students will ideally recognize that they engaged in a waterfall-like planning process (David will be explicit if students don't arrive to this conclusion on their own).

Because of the research, context and knowledge students have about this road trip, the case benefits from a high degree of certainty about future conditions and goals. This plays to the advantages of waterfall-like approaches:

Easy to measure

Easy to manage

Predictable budget

Key decisions made up front

Hierarchical alignment

In this exercise the number of unknown unknowns, and even known unknowns remains relatively small. As a result they can conduct an analysis, draft a plan, and be relatively confident in their implementation and roll out. In short, the exercise replicates the benefits of a waterfall approach.

Ultimately, students should be able to recognize that there are advantages of using waterfall, a precursor to being able to recognize when it is not an advantage to adopting it.

Segment 2 - Second Exercise: Agile – 25'

The goal of this section is to compare and contrast waterfall and agile methodologies and enable students to identify when to use each.

Purpose of this segment

In the technology world, agile-like approaches to project management have becoming increasingly popular. This approach favors incremental learning over research driven planning. Kanban's for organizing work, and short "sprints" that test hypothesis of if an idea will work are favored tools and approaches of in agile-like methodologies have become increasingly popular in name, if not always in practice. The purpose of this section is to make the distinction between agile and waterfall approaches clearer, allowing students to identify under which circumstances either might be more suitable.

Video of David teaching this segment

Exercise

Building on the previous section's exercise, David now asks a slightly different question. The groups must complete the same trip from St. Louis, Missouri to the west coast, with the important caveat: the year is now 1804. Their instructions are:

They are again planning a trip from St Louis, Missouri, to Los Angeles, California.

Should arrive as quickly as possible

Have a modest budget for supplies

Cannot detour by sea

Must make use of the same map adventurers in 1804 would have had (no internet research is allowed for this exercise)

They will have 10-15 minutes to devise a plan or strategy.

Finally, they must briefly document their plan to share with the class, specifically:

Strategy - How will they travel? What will they bring? What is their approach to the problem?

Timeline - How long will it take?

Milestones - What milestones will they set for themselves?

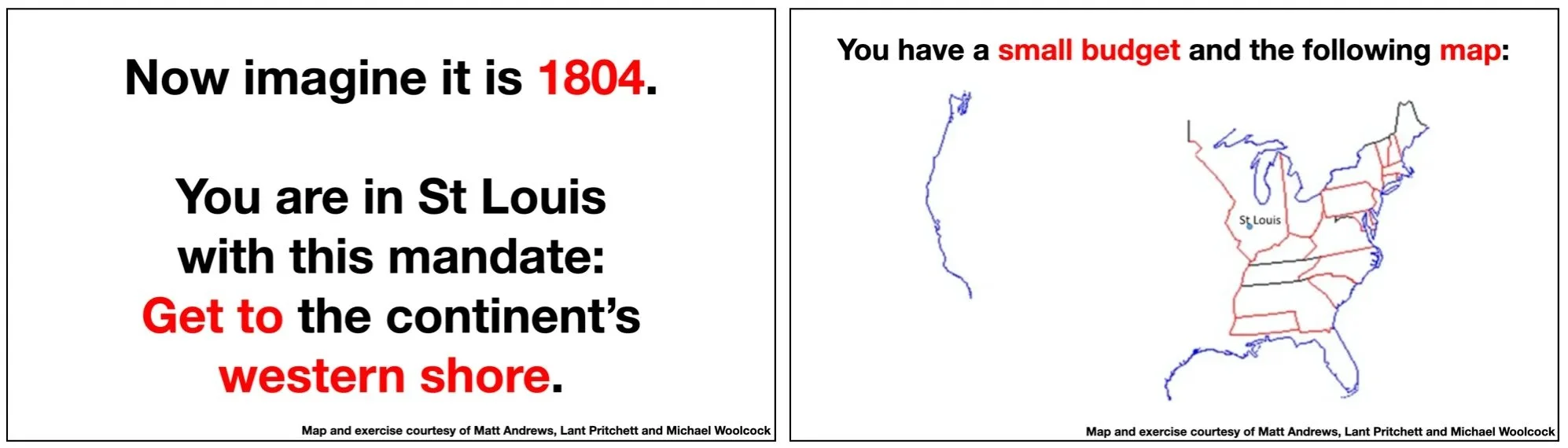

Two slides. The first says "Now imagine it is 1804. You are in St Louise with this mandate: Get to the continent's western shore". The second slide is a very partial map of the US showing a few state boundaries and no roads at all. The caption to the map says "You have a small budget and the following map."

Debrief and Discussion

In the debrief students should note that, in contrast to the high degree of certainty and ease of planning in the first exercise, it is almost impossible for an outsider to know what to expect in the second exercise.

Rather than setting milestones and determining timelines, successful teams in the second exercise will focus on how they can learn. Successful teams might, for example, try to identify peaceful and respectful ways to engage local expertise along their journey.

Facilitators should particularly be on the look out for teams that take an iterative approach. An example of this would be planning a one day journey and learning what skills they will need, acquiring them, and then taking a week long journey, then a month long and so on until they feel relatively self sufficient. As with digital era projects, this approach may be initially slower, but it lowers the risk of catastrophic failure and increases the odds of success.

Note! Even though students will talk about learning and iteration, many groups will unconsciously come up with structured plans for the trip. For example, students may say they will bring horses for travel, or wagons to bring large quantities of packed food. Much of the old growth forest in 1804 might be unnavigable by horses, and wagons presume terrain that is amenable to wheels (plus the expertise to fix them when they inevitable break). These are plans, built upon a wealth of untested assumptions that could end in tears (or, in this case, death!). This is a great opportunity to push students on what preparation via iteration versus planning looks.

A critical part of closing out this section, is conveying to students that technology projects - like traveling without a map - often have many unknowns, making them poorly suited for waterfall. Another key lesson of this exercise is it reveals how, even after doing readings on agile and adopting the vocabulary, many students will still adopt a waterfall approach when confronted with a problem with many unknowns.

Segment 3 - Implications for Governments - 15'

The goal of this section is to reflect on implications of adopting waterfall like approaches across the public sector.

Purpose of this segment

Governments are used to working with planners who specialize in waterfall-like approaches. The way public policies are usually designed and implemented follow a four stage waterfall like methodology: analyze, draft, implement and roll out. This tradition of planning has continued even as policies and services have shifted online and been digitized.

This universal application of waterfall-like approaches to project management and policy development is problematic, particularly when there is ambiguity. A waterfall approach creates risks primarily because it separates the policy and implementation teams of a single project. This severs a critical the feedback loop, preventing the policy team from learning what happens in the implementation phase. Worse, because users do not get to use a service until it is launched, problems are generally only found at the end of a project, when it is hardest and most expensive to make changes. One purpose of this section is to reflect on the problems incurred by governments when they adopt the wrong methodology.

Video of David teaching this segment

Reflections- *What does a Minimum Viable Product look like in a world with strong regulation?

How does one budget for an agile approach?

Is it always ethical to test incomplete or untested hypotheses on users?

What roles are needed to run an agile team?*

Additional key points to convey to students at this stage include:

Implementing agile like approaches also require planning: it is just that the type of planning is different. In agile the purpose of the plan is to develop and test a hypothesis from which you will learn enough information to then conduct another round of planning. If there is no plan, it's hard to know what you are learning and if you are getting closer to your goal.

A core skill of a public servant in a digital era is to be able to identify when they are in high or low uncertainty scenario and adopt the appropriate project management methodology: favoring waterfall-like approaches for high certainty and agile-like for low certainty.

Segment 4 - Examples and Wrapping Up - 10'

This sections' goal is to exemplify agile approaches in a government context.

Purpose of this segment

While agile approaches remain emergent in the public sector there exist a growing number of examples. The purpose of this section is to illustrate of how, when and why policy makers have adopted this approach.

Video of David teaching this segment

Examples

Here, David gives two examples:

Chile's government: In the early 2010s the Chilean governments digital team sought to encourage reluctant ministries to migrate citizen services online. After failing to persuade the stakeholders, the team inserted a simple survey tool to collect data from citizens and help estimate and prioritize the demand for online services. With this test, they were able to identify and focus on where demand was highest helping them both persuade ministries to collaborate with them and allocate scare resources on early exemplar projects that were most likely to succeed.

US College Scorecard: in 2015, the US government decided to create a website to help high school students decide were to go for college. The team responsible opted to ignore the specifications for the site given to them and instead adopt an agile approach. Specifically, they used mockups - printing out the website and prototyping them on a wooden phone - to test the experience and content with users. This illustrates that testing a hypothesis can be cheap and fast.

Reflections

To conclude this class, students are encouraged to reflect on past projects, why the failed or underperformed and how they might apply lessons from the class to re-imagine how they would have managed the project.

A key goal is to convey to students that their role as a public servant is to accelerate the learning process of their teams and to keep in mind that no matter the approach, execution and planning matter.

Common questions from students faculty could prepare for:

- What does a Minimum Viable Product look like in a world with strong regulation?

- How does one budget for an agile approach?

- Is it always ethical to test incomplete or untested hypotheses on users?

- What roles are needed to run an agile team?

Next Class Breakdowns by David

David teaches Unit 3 of the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age syllabus over a total of three classes. The page contains the first breakdown, here are the remaining two:

How can you get support teaching this unit?

We're dedicated to helping make sure people feel comfortable teaching with these materials.

Send a message to mailbox@teachingpublicservice.digital if you want to book in a call or have any questions.

You can also connect with David on LinkedIn.

What are your rights to use this material?

We have developed these materials as open access teaching materials. We welcome and encourage your re-use of them, and we do not ask for payment. The materials are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

If you are using any of our syllabus materials, please credit us on your course website using the following text:

We are proud to use the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age syllabus in our curriculum and teaching. Developed by an international community of more than 20 professors and practitioners, the syllabus is available open-source and free at www.teachingpublicservice.digital

Why was this page created?

This teaching material forms part of the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age project. Read more about it here.

Acknowledgements

David Eaves would like to note that this material was made possible by numerous practitioners and other faculty who have generously shared stories, pedagogy and their practices. David is also grateful to the students of DPI 662 at the Harvard Kennedy School for enriching the course and providing consent to have the material and questions shared. Finally, an enormous thank you must be given to Beatriz Vasconcellos, who helped assemble and organize the content on this page.