Digital government teaching case study

India's Open Digital Health Ecosystem: Case study of Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission

Ranjini Raghavendra

RV University, Bangalore, 2025

Introduction

This case study begins with two vignettes from the field research undertaken by the author in April 2025.

Scenario 1

At a community health centre situated on the outskirts of a city in India, a line of outpatients waits to consult with a physician. The hospital walls are covered with posters in vernacular language, promoting various government health programs. Patients carry paper-based medical records, health booklets, and handwritten prescriptions as they move forward in the queue. Caregivers, also in the queue, engage with and support the patients. During consultations lasting approximately two to five minutes, the doctor takes a brief verbal history from the patient, issues a handwritten prescription, explains their medication regimen, and advises on the timing of the next visit. All transactions remain manual, with no integration of digital tools or electronic health records.

Scenario 2

At the reception, a community health activist addresses various patient queries as he registers patients for the unique digital ID (ABHA). An elderly man, visibly unwell and without any medical documents, is directed to another doctor within the facility. Upon entering, the doctor recognizes him as a frequent visitor and examines him. The doctor then prescribes medication, calls the nurse to give him medication and urges the patient to complete pending diagnostic tests. The physician's familiarity with the patient’s condition, with the interaction lasting around five minutes, comforts the patient and healthcare delivery proceeds without the aid of any digital system. Despite good building infrastructure, adequate health staff, and daily outpatient footfall of over 300, bed occupancy is low.

Both of these scenarios unfold within the context of the implementation of Ayushman Bharath Digital Mission (ABDM), an ambitious initiative of the Indian central government to build an Open Digital Ecosystem (ODE) to act as a digital health backbone, connecting all stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem across the country. Digital systems like this one are made up of various connected components of different qualities and maturities, which governments deploy to solve societal problems. This case study focuses on the following areas:

1. Understanding the various components involved in building a massive digital public infrastructure (DPI) project like the ABDM, highlighting the various degrees of maturity for each of its components.

2. Comparing the vision of a central government agency with the realities of last mile of service delivery.

3. Analyzing the challenges public servants face when navigating through parallel processes and dealing with the legacy systems during the adoption and implementation of DPIs.

Context

Out of the 1.43 billion people in India, around 10% of the population is below the poverty line — that is, approximately 143 million people (2024). The total health expenditure of India amounts to 3.3 % of its GDP, with over 50 lakh healthcare professionals and over 12 lakh healthcare facilities. In India, 30.1% of medical consultations are conducted in the public sector. Private doctors in clinics and private hospitals account for the remaining 42.5 % and 23.3%, respectively.

There are several problems plaguing the healthcare ecosystem in India. Out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenses account for about 62.6% of total health expenditure, one of the highest in the world. High OOP health expenditures push many households into poverty (Sriram & Albadrani, 2022). Although there have been initiatives to provide health insurance for different sections of society, the coverage is still dismal.[2]

The healthcare sector in India is riddled with extremely complex processes involving multiple stakeholders and touchpoints. Disparate entities demand that patients go to multiple providers individually. India has a large population with a complicated, inequitable distribution of healthcare resources. Within the public health sector, there are multiple government programs with different processes for enrollment and receiving benefits. In addition to this, paper-based health records are used, and there often is no system to maintain long-term digital records.

India in the Digital Age

Digital public infrastructures (DPIs), beginning with Aadhar and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), have revolutionized the delivery of public services in India. DPI refers sets of software that can act as an intermediate platform layer between physical technologies such as data centers and application layer (Rodriguez, S, Price, & Rodriguez, A. (2023) in Nagar and Eaves (2024). They suggest three types of DPI that are common: (1) Digital Identity Systems (2) Digital Payments and (3) Data Exchange Systems.

The next paradigm shift being attempted today builds on the DPIs, focusing on creating open digital ecosystems rather than following the traditional monolithic technological systems approach (Viswanathan, Guha & Pasumarthi, 2022). ABDM is envisioned as analogous to Aadhaar and UPI, aiming to transform healthcare delivery.

Over the last decade, India has pioneered a new approach to building government technology (GovTech) , that prioritizes the creation of technology “building blocks” that multiple innovators can leverage to build citizen-centric solutions. In other words, an approach that focuses on creating open ecosystems instead of closed systems. While GovTech 1.0 was focused on the “automation”o f processes such as online applications, GovTech 2.0 progressed towards providing end-to-end digitization of public service delivery by “building systems.” The present phase of GovTech 3.0 is focused on breaking down siloes and creating “enabling ecosystems” (Viswanathan, Guha & Pasumarthi, 2022).

Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission

The Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) is an initiative by the Government of India (GoI) to facilitate exchange of health information among various stakeholders, both in the private and public healthcare sector. The vision of ABDM is “to create a National Digital Health Ecosystem that supports Universal Health Coverage in an efficient, accessible, inclusive, affordable, timely and safe manner, through provision of a wide range of data, information and infrastructure services, leveraging open, interoperable, standards‐based digital systems, and ensuring the security, confidentiality and privacy of health‐ related personal information.”(National Health Authority. (n.d.)

The mission is “to create a digital platform for evolving the health ecosystem through a wide range of data, information and infrastructure services while ensuring security, confidentiality and privacy” (NHA, 2022). The National Health Authority started implementing Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (earlier known as the National Digital Health Mission) in the six union territories on August 2020, and it was rolled out throughout India on September 27, 2021. By utilizing India's established digital public goods, like the Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile (JAM) trinity and open & interoperable standards, ABDM facilitates data exchange between the intended stakeholders on the ABDM network after the patient’s consent.

So, through ABDM compliant applications, patients will also be able to choose which health records they want to link with their ABHAs, (Ayushman Bharat Health Accounts), store their health records on their devices, access their records online, and share their health records with healthcare providers. Due to federated architecture ABDM does not store any health data instead it is always created and stored by healthcare providers. Only the data collected for registries such as the ABHA registry, the Healthcare Professional Registry and the Health Facility Registry (HFR) is stored centrally. Storing these datasets centrally is necessary since they are essential to provide interoperability, trust, identification and a single source of truth across different digital health systems.

Key components in the ABDM Ecosystem

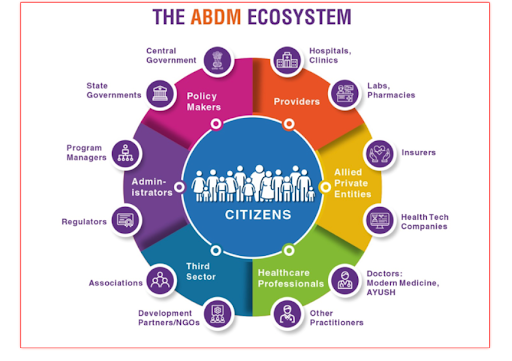

To foster a unified digital health ecosystem across India, the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) is building the foundational infrastructure. This includes delivering secure, confidential, and private health data, information, and infrastructure services through a comprehensive, open, interoperable, and standards-based digital system. The key stakeholders are described in the figure below.

Figure 1 (Source: NHA)

The six key components of ABDM[3] (NHA, 2021) are:

ABHA ID: Unique 14-digit identifier for individuals.

Healthcare Professional Registry (HPR): Verified directory of professionals.

Health Facility Registry (HFR): Directory of healthcare facilities.

Universal Health Interface (UHI)

Health Information Exchange and Consent Manager (HIE): Consent-based data sharing.

Health Claims Exchange (HCX)

Figure 2 (Source: NHA)

1. Ayushman Bharat Health Account (ABHA) ID: The Aadhar Act provides for the use of Aadhaar numbers as proof of identity of a person. While the Aadhaar Act allows for the use of Aadhaar numbers for identity verification, its mandatory linkage is specifically for Direct Benefit Transfers. For other purposes, Aadhaar holders can only use their number voluntarily to establish identity. Hence a health identifier such as ABHA is conceptualised. ABHA IDs themselves don't provide healthcare services, but they are instrumental in securely linking an individual's health records across all hospitals, whether government or private.All citizens of India can create an ABHA.

It's also important to distinguish ABHA from the Ayushman Card, both of which are initiatives of the National Health Authority (NHA).

2. Healthcare Professionals Registry: The Healthcare Professionals Registry is a repository of healthcare professionals across all the systems of medicine, both modern and traditional. It includes doctors from all systems of medicine, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals. Registration of doctors across Modern Medicine, Dentistry, Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa and Homeopathy has been included in the Healthcare Professionals Registry.

3. Health Facility Registry: The Health Facility Registry is a comprehensive repository of all the health facilities, both public and private, across both modern and traditional systems of medicine. These include hospitals, clinics, diagnostic laboratories,imaging centers and pharmacies. The HFR contains available service attributes for each facility.

4. Universal Health Interface (UHI): The UHI is envisioned as an open protocol for various digital health services. The UHI Network will be an open network of End User Applications (EUAs) and participating Health Service Provider (HSP) applications. UHI will enable a wide variety of digital health services between patients and health service providers (HSPs) such as booking OPD appointments at hospitals and clinics, booking tele-consultations, checking availability of critical care beds, searching for lab and diagnostic services, or booking of home visits for lab sample collections.

5. Health Information Exchange and Consent Manager (HIE-CM): The HIE-CM manages consents related to personal health data and supports the exchange of interoperable health data across ecosystem players. The consent manager will manage consent and data requests between Health Information Providers (HIP, any healthcare provider who creates health information in the context of providing healthcare-related services to a patient) and Health Information Users (HIU, any entity that would like to access health records of an individual). HIE-CMs are envisaged to act as a conduit for an end-to-end encrypted and consented data exchange. This will be to ensure that no individual data is shared without user consent. All exchanges need the individual to authorize access to relevant Health Information. This authorization is achieved with the consent manager framework.

6. Health Claims Exchange (HCX): The HCX aims to streamline and standardize health insurance claim processing. It serves as a gateway for exchanging health claim information among insurers, third-party auditors, healthcare providers, beneficiaries, and other relevant entities and ensures interoperability, machine-readability, auditability, and verifiability. This system aims to enhance efficiency and transparency in the insurance industry and benefit policyholders and patients.

The ABDM stack aims to create an interoperable ecosystem to facilitate the exchange of healthcare data, connect various healthcare systems, and overall improve access to digital health services (see Appendix 1).

So far, we have discussed the key components of ABDM. The following sections will focus on analyzing the challenges and dilemmas public servants face due to legacy systems and processes while implementing strategies to improve adoption of ABDM. The author of this case study conducted in-depth interviews with eight public servants, including three medical officers, two Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), two Primary Health Centre Officers, and an Arogya Mitra, who assists citizens in accessing public healthcare.

In-depth interviews with this team of public servants helped the author analyze the dilemmas they are currently facing, as well as the status of the implementation of ABDM. The research field site is a town and a village about 50 km outside the city of Bangalore, India. The health sector is unique in terms of implementing a programme or managing a disease as it involves various components and different health functionaries. While discussing the public servants' dilemma in the section below, note that the discussion involves understanding the challenges faced by the team of health functionaries and not only one official.

The Public Servants' Dilemma

In 2021, the Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi addressed the nation, sharing that the country’s seven-year campaign to strengthen its health facilities was entering a new phase. “Today, we are launching a mission that has the potential of bringing a revolutionary change in India’s health facilities. The ABDM will now connect the digital health solutions of hospitals across the country with each other," he said. (NHA, 2022).

While this is the vision of the higher central agencies, after four years, the knowledge and practice regarding ABDM remains very low compared to other digital government initiatives, with major concerns related to data security and privacy (Arjun et al, 2024).

A medical officer who heads a primary health centre was optimistic while remaining pragmatic about digitization and ABDM. He said:"This is social engineering. We have many national and state specified health programs. All these different programs, websites, processes and technologies need to be integrated and made interoperable. This is not so seamless. During a NCD [Non-Communicable Diseases] drive, enrollment of the whole population was attempted in one taluk. It was quite ambitious. Digitization is necessary, but given the limited manpower, limited IT infrastructure such as hardware, internet connectivity, servers and old mobile devices that are not upgraded, this is a huge challenge as of now."

The foremost challenge is that manydigital health initiatives have already been implemented by different state governments and health programs over the last decade. They each have different degrees of maturity and adoption rates. ABDM has limited interfaces with these systems. Integration and operationalizing interoperability with existing systems on the ground is extremely complex. According to the FICCI-BCG 2020 report cited by World Bank (2023), it is estimated that there are over 500 software providers who provide HMIS software to hospitals, while the adoption of Electronic Health Records (EHR) in India is less than 10% and is characterized by fragmentation and low digital penetration.

Raj, Dananjana et al (2023) note that the success of ABDM will depend on its integration with other government-managed health applications, such as the integrated disease surveillance program module of the Integrated Health Information Platform, a digital decentralized state-based surveillance system,the Mera Aspatal (My Hospital) patient feedback system, NIKSHAY, an online tuberculosis patient monitoring application, and many others.

Doctors and Digitization

The National Health Authority. (n.d.) notes that a clinic with only OPD should have a module for the registration of patients, OP examination and prescription. In addition to these modules, HMIS for large tertiary care centres should also have modules for laboratory, radiology, pharmacy, in-patient care, discharge, and other functions. However, observations by the author of this case study revealed that many of the processes in these clinics are still manual. Digitization has been slow in the doctor's room of primary and community health centres, with appointments, health records, prescriptions, and referral systems all remaining manual. "We are still in the manual era here at these centres, [digitization] might happen in the future," said a medical officer.

While the author was interviewing the Arogya Mitra, a caregiver walked up to him asking for details about how to procure eye drops and medicines for his mother. The Arogya Mitra suggested that he take a registration sheet manually from the doctor and give it to the pharmacist.

However, the National Health Authority. (n.d.) specifies the following: Once the OPD registration is done, the same demographic details (name, age, gender, address, etc.) will not require repeated entry during the OPD consultation, and they should be auto-populated and reflected on the screen of the treating doctor. Once the doctor writes a prescription for certain medicines, the pharmacist in the pharmacy should be able to see the prescription. The doctor's diagnosis should be accurately reflected in the in-patient module before the patient is transferred to the ward, and subsequently included in the discharge summary. Such integration ensures a smooth and efficient workflow.

However, this scenario did not play out in the community health centre that day. The doctors did not have any computers in their room during their examination of patients. While some processes were digitized, others were not as, digitization is fragmented. In addition to this, different health programmes have different information systems. A primary health officer explained that there are parallel information systems that she uses daily. She said: “It is double or triple work, doing both manual and digital systems. Take the example, vaccinations. We have to enter all the details manually in the book, enter it in the RCH (Reproductive and Child Health) portal and also in the UWinApp. We have informed our seniors about multiple systems and have been told that these work processes would be streamlined.”

However, the National Health Authority. (n.d.) (p35) specifies that "digitization of health should not lead to unnecessary and undesirable efforts for additional data entry. As far as possible, the health data that is generated should be digitized during the process itself and not by way of an additional step or effort after the process.

When asked about these multiple IDs and her use of ABHA ID, the primary health officer added: “ABHA IDs are being created at the sub-centre level. We are creating ABHA IDs while pregnant women register for prenatal care. There is another option to create ABHA IDs through NCD App (Non-Communicable Diseases). However, we do not use this ABHA ID much. We instead use mobile numbers for searching, as patients remember this. Each mobile number can take up to two registrations.”

Registration of ABHA is being conducted by a health activist called 'Arogya Mitra'. They act as an intermediary between the public health facilities and the public, helping the public in creating awareness about ABDM. One Arogya Mitra explains: “Our main job is creating awareness, assisting citizens to access healthcare and (digitization) doing it online. We Argoya Mitras go to meetings every week at Gram Panchayats (Village-level Local Bodies) at various locations. We also operate at the Community Health Centre, Taluk Hospital and District Hospital. We connect patients with these hospitals. In this hospital alone, I have helped create 10,000 plus ABHA IDs over the last six months. There are 1650 procedures that are covered by the insurance scheme Ayushman Bharat. If the facility cannot provide them the health care or conduct the surgery, they are referred to the private or government hospitals. They need referral letters from the health facility as well as ABHA ID to recieve free treatment.”

Here, the Arogya Mitra is explaining about the Ayushman Bharat Insurance scheme and its interconnections with the digitization process and ABHA.

Actions and Reactions

Adoption and Implementation of ABDM

The first scenario presented at the beginning of this case study focused on the author's observations at the Out Patient Unit of a community centre, where the processes were manual. The ABDM has introduced a “Scan and Share” facility that offers QR-code registration in ABDM empanelled facilities, where patients can scan QR code to share their demographic details and health records. The aim is to minimize the problem of long queues at health facilities and the entry of incomplete and inaccurate data. The author did not see any QR codes displayed in the waiting and registration area during her visit to the community centre.

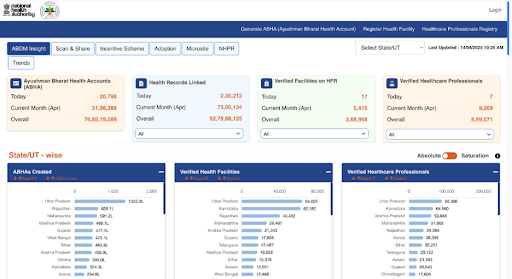

The ABDM Dashboard provides open data with daily updates on the adoption of ABDM. The following are some of the indicators that are tracked to analyze the adoption rates of ABDM: ABHA created by state, by gender, and by age-wise; health records linked (private and public);verified facilities in theHealth Facility Registry (private and public);health care professionals (doctors and nurses);health records linked.

Analysis of this data reveals that the adoption of ABDM is poor across many states and across the different components of ABDM. Different states have varied levels of health systems with differing maturity levels of these ABDM components. Mishra et al (2024) note that the federal structure of governance and differential strength of multiple health systems have adversely influenced the implementation of ABDM. This is apparent from the slow pace of HPR and HFR registrations across the country.

In order to improve adoption and expand the implementation of ABDM, a scheme called the Digital Health Incentive Scheme was launched to encourage the adoption of digital health technologies by offering financial incentives to various stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem. These incentives were designed to promote the digitization of patient records, facilitate ABHA-linked record sharing, and boost the overall digital health infrastructure. The scheme provides financial rewards for healthcare facilities, digital solution providers, and other players for using ABHA-linked records and digital health solutions.

Medical officers who are public health managers of their facilities face a number of challenges whenintegrating into the healthcare ecosystem as envisioned in ABDM. Many primary and community health centres have yet to digitize their work processes. Their appointments and prescriptions are manual.

"In many health facilities, hardware and software are inadequate. In small health units, there has been no budget to upgrade IT infrastructure or invest in digital storage space, a prerequisite for ABDM. In remote areas, connectivity is poor. Medical officers and health staff have to prioritize clinical care and hence have limited time and staff to implement ABDM," said one medical officer.

Stakeholders such as the older patient mentioned in scenario 2, will find it difficult to adopt digital health initiatives. Senior citizens require maximum healthcare, and learning digital health techniques will be extremely challenging. This is sometimes called the “grey divide.” The poor and the illiterate will also be excluded due to "intervention-generated inequity."

Further Reflections

India is a pioneer of digital ID systems. The question that comes up is why Aadhar can’t be used instead of creating new ABHA IDs for the entire population of India. In Section 7 of the Aadhaar and Other Laws (Amendment) Act, 2019, clearly states that, “Every Aadhaar number holder, to establish his identity, may voluntarily use his Aadhaar number in physical or electronic form by way of authentication or offline verification, or in such other form as may be notified, in such manner as may be specified by regulations.” The Aadhaar Act provides for the use of Aadhaar number as proof of identity, subject to authentication. However, the mandate of mandatory linkage of Aadhaar is restricted to recieving only Direct Benefits Transfers (DBTs) and can’t be used for any other purpose. Since Aadhar is only for DBTs, it has become necessary to create another exclusive ID for the health sector.

Other stakeholders such as experts in the field believe that, although the national digital health architecture points to both the public health system and insurance, what is being implemented is more “aligned to an insurance-based model where the focus is on exchange of health records for care coordination across public and private sector and for insurance-type reimbursement, which is not the same as creating a health information exchange for public health where both public and private providers share data.” (Sundararaman, 2024)

While COVID-19 vaccination apps like Aarogya Setu and later CoWIN brought digital public health infrastructure closer to citizens, such instances of large-scale and rapid adoption of digital health technologies remain very rare in India.

Conclusion

Union Minister of State for Health and Family Welfare, Prataprao Jadhav, shared the following update in a written reply to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian Parliament, on February 6, 2025. The following data on the status of implementation and adoption of ABDM was also presented in the report.

“About 5.64 lakh healthcare professionals are listed in the HPR. 1.59 lakh facilities are using ABDM-enabled digital software. These numbers span 36 States/Union Territories and 786 districts, including rural areas. The focus of the Ministry of HFW has been on inclusion and accessibility. The ABDM supports integrated digital healthcare across primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. ABDM aims to ensure interoperability of health data and to create lifelong digital health records for every citizen. It emphasizes inclusion through (1) Enhanced access in remote areas via telemedicine and other digital tools; (2) Multilingual and user-friendly ABHA and PHR apps (e.g., ABHA app, Aarogya Setu) (3) Offline and assisted ABHA registration modes to address limited digital access and literacy.”

These numbers point out that the adoption of ABDM by health care professionals, both in the public and private sectors, and by health facilities, has been poor. Awareness among different stakeholders on the value and implementation methodologies is dismal across different states in India. M C Arjun et al suggest that there is a need to increase the information, education and communication (IEC) about ABDM by developing new strategies to create awareness and disseminate the correct information.

The success of ABDM will depend on the mass awareness, and a huge mobilization effort to promote its adoption and generate demand. However, as of now, the reach of ABDM is small and has very little to offer to the public managers and stakeholders. For example, ABHA is not linked to entitlements in many states. In most cases, during OPD registration, mobile numbers are used as identifiers. The absence of dedicated legislation on data privacy and confidentiality remains a significant gap. There is an urgent need to address consent and privacy issues in greater detail, along with stronger efforts by public administrators to promote awareness and increase enrollments.

Currently, the ABDM’s digital infrastructure is largely oriented towards enabling health insurance services, with future plans to incorporate integrated care management networks. In summary, the ABDM presently has limited impact on strengthening healthcare delivery or contributing to public health information infrastructure, which largely continues to operate independently of the ABDM framework.

Appendix 1: Representation of ABDM architecture with modular and interoperable aspects.

(Source: NHA)

Appendix 2

References

Arya, A. (2024). A study on evaluating the role of Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) in enhancing healthcare accessibility and affordability. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4799196

Arjun, M. C., Poorvikha, S., Kurpad, A. V., & Thomas, T. (2024). Knowledge, attitude and practice about Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission and digital health among hospital patients. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 13(10), 4476–4481. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_255_24

Kamath, R., Banu, M., Shet, N., Jayapriya, V. R., Lakshmi Ramesh, V., Jahangir, S., Akthar, N., Brand, H., Prabhu, V., Singh, V., & Kamath, S. (2025). Awareness of and challenges in utilizing the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission for healthcare delivery: Qualitative insights from university students in Coastal Karnataka in India. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 13(4), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13040382

Kamineni, S., & Bishen, S. (2025, January 15). India can be a global pathfinder in digital health – here’s how. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/india-can-be-a-global-pathfinder-in-digital-health-here-s-how/

Kharbanda, V., Linnenbank, P., Singh, B., Sahoo, P., Mahajan, P., & Sethia, M. (2024). Catalyzing digital health in India: Critical pathways for user adoption & driving the next wave of transformational use cases. Arthur D. Little & NATHEALTH. https://www.adlittle.com/en/insights/report/catalyzing-digital-health-india

Kudva, R., Pande, V., & Mittal, K. (2022). Widening India’s digital highways: The next frontiers for open digital ecosystems (ODEs). Omidyar Network India. https://www.omidyarnetwork.in

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. (2019). National digital health blueprint (NDHB). Government of India. https://abdm.gov.in/home/publications

Mishra, U. S., Yadav, S., & Joe, W. (2024). The Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission of India: An assessment. Health Systems and Reform, 10(2), 2392290. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2024.2392290

Nagar, S., & Eaves, D. (2024). Interactions Between Artificial Intelligence and Digital Public Infrastructure: Concepts, Benefits, and Challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.05761. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.05761

Narayan, S., Seth, P., & Shrivastava, D. (2024). Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission: An initiative of digital transformation towards healthcare. In Proceedings of the Twenty Second AIMS International Conference on Management (pp. 1602–1610). Amity University & Indian Institute of Travel and Tourism Management.

National Health Authority. (n.d.). A brief guide on Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) and its various building blocks. Government of India.

Paliwal, S., Parveen, S., Singh, O., Alam, M. A., & Ahmed, J. (2023). The role of Ayushman Bharat Health Account (ABHA) in telehealth: A new frontier of smart healthcare delivery in India [Preprint]. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2961416/v1

Pasumarthi, B. (2022, August). Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission: India’s healthcare ODE (DigiStack Case Study). The Quantum Hub. https://www.thequantumhub.com

Prasad, S. S. V., Singh, C., Naik, B. N., Pandey, S., & Rao, R. (2023). Awareness of the Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana in the rural community: A cross-sectional study in Eastern India. Cureus, 15(3), e35901. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35901

Raj, G. M., Dananjayan, S., & Agarwal, N. (2023). Inception of the Indian Digital Health Mission: Connecting the dots. Health Care Science, 2(5), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/hcs2.67

Samudyatha, U. C., Kosambiya, J. K., & Madhukumar, S. (2023). Community medicine in Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission: The hidden cornerstone. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 48(2), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_343_22

Sharma, A. (2024, January 17). Navigating the Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM) ecosystem: A roadmap to digital health. Medlr. https://medlr.in/blog/navigating-the-abdm-ecosystem-a-roadmap-to-digital-health/

Velan, D., Mohandoss, H., Valarmathi, S., Sundar, J. S., Kalpana, S., & Srinivas, G. (2024). Digital health in your hands: A narrative review of exploring Ayushman Bharat's digital revolution. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 23(3), 1630–1641. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2024.23.3.2762

Viswanathan, A., Guha, D., Pasumarthi, B., & Kumar, R. (2022, March). Building digital ecosystems for India: An implementation blue book. The Quantum Hub. https://www.thequantumhub.com

World Bank. (2023). Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission’s integrated digital health ecosystem is the foundation of universal citizen-centered health care in India.

[1] https://abdm.gov.in/microsites/100microsites